Swissinfo 2006:

9. Juni 2006 - 10:31

Sir Peter Smithers 92-jährig im Tessin verstorben.

MORCOTE - Sir Peter Smithers ist tot. Der ehemalige englische Minister und langjährige Generalsekretär des Europarates ist am Donnerstag im Alter von 92 Jahren im Tessin verstorben. Am kommenden Montag wird der Ex-Diplomat auf dem Friedhof von Lugano bestattet, wie seine drei Kinder in einer Todesanzeige bekanntgaben. Seit seiner Pensionierung im Jahr 1969 lebte Smithers in Vico Morcote am Luganersee, wo er zum Ehrenbürger ernannt wurde. Hoch über dem See baute er im Laufe der Zeit eine traumhafte Parkanlage auf. Im April 2001 erhielt er dafür vom Schweizer Heimatschutz den Schulthess-Gartenpreis.

Der am 9. Dezember 1913 in Yorkshire geborene Ex-Diplomat machte sich im Tessin nicht nur als Botaniker, sondern auch als Fotograf einen Namen. Im März 2004 wurden seine Bilder an einer Ausstellung in Bellinzona gezeigt. Im vergangenen Jahr starb seine Frau Dojean, mit der er seit 1943 verheiratet war. Während des Zweiten Weltkrieges war Peter Smithers Navy-Attaché in Washington gewesen. In den Fünfzigerjahren wurde er zum Minister für die britischen Kolonien ernannt. Von 1964 bis 1969 war er Generalsekretär des Europarates.

"Ich bin dankbar für jede Minute, die ich erlebt habe. Was will ich mehr?", sagte Smithers wenige Tage vor seinem Tod gegenüber dem "Corriere del Ticino". "Den nahenden Tod empfinde ich nun als Befreiung." SDA-ATS

Times online:

http://timesonline.typepad.com/gardening/2006/06/sir_peter_smith.html

Times online:

Telegraph:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?view=DETAILS&grid=&xml=/news/2006/06/10/db1001.xml

New York Times:

Peter Smithers Dies at 92; Spy With a Green Thumb

By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Sir Peter Smithers, who saw his work as a lawyer, politician, diplomat, scholar, photographer and spy as distractions from his passion for growing glorious gardens, died on June 8 in Vico Morcote, Switzerland. He was 92.

Sir Peter's death was announced by the Council of Europe, for which he once served as secretary general, and the American Clivia Society, which noted that he had developed two new varieties of lilies.

As a spy in World War II, he worked for Ian Fleming, who went on to create the fictional spy James Bond, and British obituaries did not ignore the possible connection.

But neither Mr. Fleming nor his biographers ever confirmed any of the many rumored Bond originals, and Sir Peter was never prominent among them. A chap named Smithers, however, did appear as one of Q's assistants in "For Your Eyes Only" and "Octopussy," and another Smithers was a villain in "Goldfinger."

Arguably, though, Sir Peter was to gardening what Bond was to martinis. The Royal Horticulture Society gave him one of its highest awards, the gold Veitch Memorial Medal. His garden in Switzerland — with 10,000 plants, none a duplicate — won a prize for being the best in that country in 2001. The Financial Times said it was named one of the 500 greatest gardens since Roman times.

His lush photographic images of flowers won eight gold medals from the horticultural society, where some of them hang. They have been called "floral pornography."

Sir Peter fleshed out this idea in an interview with The New York Times in 1987.

"This is Playboy in flowers," he said. "What are flowers but sex in action? The bee performs the wedding. I take the pictures on the wedding day. Two days later, the flowers are exhausted."

Peter Henry Berry Otway Smithers was born in Yorkshire on Dec. 9, 1913. He grew up hanging around potting sheds, spending spare change on plants. His nanny was a fervent naturalist who fed him fried blackbird eggs and hedge trimmings.

At 13, he persuaded the Royal Horticultural Society to let him attend the Chelsea Flower Show, the first child to do so, The Guardian said. At his public school, Harrow, he began an index of every plant and seed packet he acquired; it grew to 32,000 entries by his death.

He wrote that he "fell for lilies in a big way" while in school.

Lilies "win your love with their beauty and grace and a certain indefinable allure: and then they break your heart in the end," he wrote. "It is a very old story."

Another among his other oft-repeated quotations: "I consider every plant healthy until I've killed it myself."

He won highest honors in modern history at Oxford, then became a lawyer. He was commissioned into the naval reserves in 1939. Measles landed him on shore duty.

He served with Mr. Fleming in France, then helped round up German spies in Britain. Sent to Washington, he worked in naval intelligence. He went to Mexico and Panama to monitor U-boat communications.

His agronomy suffered during the war, particularly his little garden in Georgetown. In Mexico and Central America, he raised orchids between espionage assignments.

After the war, Sir Peter earned a doctorate from Oxford with a dissertation on Joseph Addison, the 18th-century English essayist who fulfilled his wish of dying on a beautiful day in June in his thriving garden. So did Sir Peter.

After some jobs in business, Sir Peter won a seat in the House of Commons. He enjoyed meeting with his rural constituents as he tended his tulips. He found time to create a magnificent garden in the shadow of Winchester Cathedral, as well as to raise more than 2,000 kinds of cactus in a greenhouse.

In the 1960's, he was a British delegate to the United Nations and served as a junior minister in the Foreign Office. From 1964 to 1969, he was secretary general of the Council of Europe, the first Briton to hold the post.

Harold Wilson, the Labor Party leader, supported his elevation to the House of Lords, but Edward Heath, the leader of Sir Peter's own Conservative Party, vetoed it; the two disagreed about foreign policy.

Instead, Sir Peter was knighted in 1970. But the political disappointment, plus a feeling that standards were declining in Britain, prompted him to accept an offer of Swiss citizenship and buy an old terraced vineyard on a hillside overlooking Lake Lugano. His garden there, conceived as an ecosystem of exotic plants, included hybrids he developed himself.

The garden achieved its goal of requiring less work as it and its owner matured — a philosophy articulated in Sir Peter's book, "Adventures of a Gardener," published in 1995. A part-time gardener is now needed just once a week in season, and twice a week in winter.

Sir Peter's wife, the former Dojean Sayman, for whom he bred and named a white tree peony, died this year. He is survived by their two daughters and a stepson.

Years ago, Sir Peter began giving away his plants. He said he believed that the pleasure of owning a fine plant was not complete until it had been given to a friend.

biography,

copied from the website.

of the Botanical garden

Sir Peter Smithers:

Biography

by Sir Peter Smithers

* 9.12.1913. - † 8.6.2006

I

was born in Yorkshire, England, in 1913. 1 was brought up by Nanny

and Granny during World War 1, my parents both being absent on war

duty. Nanny was a keen naturalist and I contracted a gardening

virus at that early age. It has never left me to this day.

When

at school at Harrow I began an index of every plant and packet of

seeds I ever acquired, a practice which continues to this day, the

numbers now being in the 32,000 range. While at Harrow I fell for

lilies in a big way and began growing Lilium sulphureum. Fifty

years later I visited Burma, recovered bulbs of that lily and

began breeding from it, later registering two grexes and one clone

and distributing the seed. While at Oxford I became a fellow of

the Royal Horticultural Society and am now an Honorary Fellow with

the Veitch Memorial Medal in Gold for contributions to

Horticulture.

World War II did

not entirely interrupt my gardening as might have been expected.

At sea in the winter of 1939 1 was gravely ill and when

recovered was invalided to shore duty, first in France whence I

got away two days before the collapse of that country and the

armistice with the Germans, then in London on security duty at the

time of the parachute landings by German agents, then as Assistant

Naval Attache at the British Embassy in Washington in charge of

the exchange of Naval intelligence between the Admiralty and the

Navy Department. My small garden in Georgetown was a failure: too

busy with the war. But then I was appointed acting Naval Attache

in Mexico, Central America and Panama, obliged to travel widely

monitoring possible submarine shore contacts. It was a gardener's

idea of heaven, and I made a small garden in Cuernavaca replete

with orchid species, palms and aroids and also collected palm

specimens for the British Museum Herbarium. But, more importantly,

in Mexico in 1943, 1 collected a wife, Dojean Sayman, of St.

Louis, Missouri, who has put up with my gardening habits and other

failings ever since.

Back in England after the war, and a

Member of Parliament, I took over the garden of my late father at

Itchen Stoke, and then moved to that of my late mother in

Winchester, Colebrook House, next to the Cathedral, where I made a

garden based upon the three medieval streams which ran through it.

Orchid growing continued in a greenhouse built off the dining

room.

For a time I was a member of Parliament for

Winchester and Under-Secretary of State in the Foreign Office. I

later resigned from Parliament and the Government when elected

Secretary-General of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg. There I

made a garden in the Official Residence, working for the first

time in a continental climate.

On retirement from

Strasbourg my wife and I built a house and made a garden at Vico

Morcote, Switzerland, above Lake Lugano, in one of the best

gardening climates in Europe, where an extremely wide range of

plants can be grown successfully. Here the specialties were

magnolias, of which I registered the hybrid 'William Watson', tree

peonies, of which I registered a number of hybrids bred from

Paeonia rockii, and the lily hybrids mentioned previously. The

garden was stuffed full of bulbous plants of every kind including

hybrids of Amaryllis belladonna. In the greenhouse I continued an

ambitious breeding program in Nerine sarniensis, which ended in

1995 when the program was sold to Exbury, from which famous garden

so many of my parent plants originated, and where it is being

continued with enthusiasm by Nicholas de Rothschild.

Though

the garden at Vico Morcote contained many specialist collections,

it was conceived as an ecosystem of exotic plants in which the

plants themselves would do most of the work. The work load would

diminish as the owners grew old. This, in fact, worked out

successfully and the garden is now easily maintained with the help

of a part time gardener twice a week in season and once a week in

winter. Out of the garden at Vico Morcote there grew a

photographic activity, based on the plants growing in the garden.

This won eight Gold Medals for Photography from the Royal

Horticultural Society and resulted in 23 one-man shows of

photography, mostly in the United States, including one at the

National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. Writing in

Country Life, the President of the Royal Horticultural Society,

Sir Simon Horby, wrote: "Sir Peter may have some equals round

the world as a gardener, but probably none as a plant

photographer".

I regard gardening and plants as the

other half of life, a counterpoise to the rough-and-tumble of

politics. When the telephone at Colebook House rang with Downing

Street on the other end asking whether I would agree to join the

MacMillan Government as a Minister in the Foreign Office, I was

busy pruning my standard roses. But I accepted with delight! When

my constituents would visit me in the garden at Colebrook House at

the weekend to present their problems, I was likely to say "All

right, tell me about it while I plant these tulips: I must get

them in before it rains". This was well understood in a

country constituency and tended to gain votes rather than lose

them. Also it was good for the tulips. So life was a harmonious

whole of two contrasting halves. Now, at age 83 (1997), 1 work

less in the garden and much less in politics, but thanks to the

imaginative initiative of the International Bulb Society in

setting up the "bulb robin", I am gardening on the

Internet and greatly enjoying it.

1997

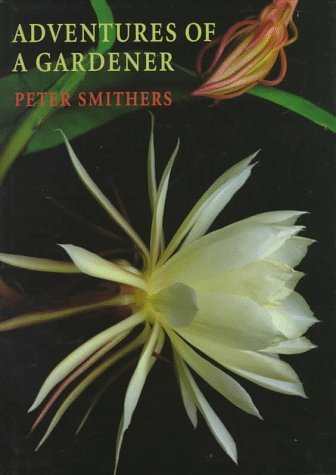

Sir Peter Smithers: Adventures of a gardener.

Gebundene Ausgabe

- 211 Seiten - Harvill Press

Erscheinungsdatum: 1. Mai

1996

ISBN: 1860460593 [Sir

Peter beschreibt in diesem Buch ausführlich seine

Leidenschaft zu den Pflanzen, auf mehreren Seiten auch ausführlich

über Päonien und seine eigenen Züchtungen]

more infos:

http://www.ticino-tourism.ch/15/common_details.jsp?lang=de&index=3&menuId=_5850&id=32673

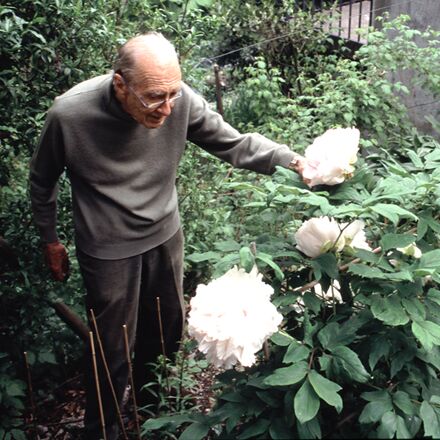

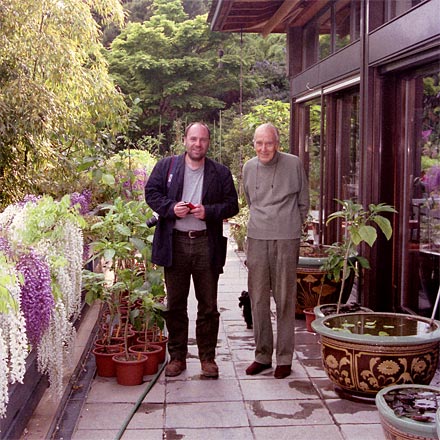

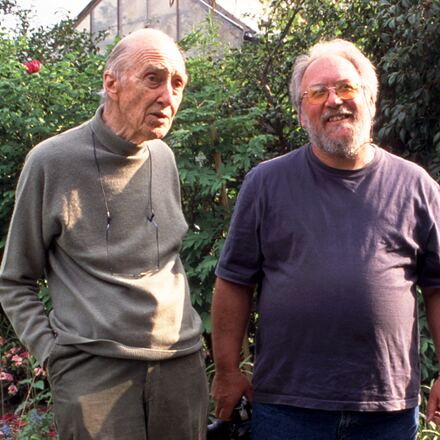

pictures made during my visit to Sir Peter in April 2002:

Sir Peter shows us his peony collection and tells interesting stories about his breedings

Sir Peter and me on the terrace of his house

Sir Peter with my guest from Australia, Denis Wilson

Hesperus